ARTHROLOGY (SYNDESMOLOGY)

Written By Anjani Mishra

What is joints ?

An articulation or joint is formed by the union of two or more bones or cartilages by other tissue. Bone is the fundamental part of most joints; in some cases a bone and cartilage, or two cartilages, form a joint. The uniting medium is chiefly fibrous tissue or cartilage, or a mixture of these two. Some joints have no movement, some have slight movement and some are freely movable.

How joints are classified ?

Joints

may be classified:

A) Anatomically, according to their

mode of development, the nature of uniting medium and the form of joint

surface;

B) Physiologically, with regard to

the amount and kind of movement or the absence of mobility in them; and

C) By a combination of the foregoing

conciderations.

Joints vary in both structure and arrangement and are often specialized

for particular functions. However, joints have certain common structural and

functional features and may be classified into three types:

A) Fibrous joint -

formerly known as a synarthrosis;

B) Cartilaginous joint -

formerly known as an amphiarthrosis; and

C) Synovial joint -

formerly known as a diarthrosis.

A. FIBROUS JOINTS

In

this group the segments are united by fibrous tissue in such a manner as to

practically preclude movement; hence, they are often termed fixed or immovable joints.

There is no

joint cavity. Most of these joints are temporary, the uniting medium being

invaded by the process of ossification, with a resulting synostosis. The chief classes in this group of joints are as

follows:

What do you mean by Surure ?

(1)

Suture- The

term suture is applied to those joints in the skull in which the adjacent bones

are closely united by fibrous tissue- the sutural ligament. It is further

classified into:

(a)

Sutura serrata:-

In this case the edges of the bones have irregular interlocking margins. e.g.,

the interfrontal suture.

(b)

Sutura squamosa:-

In this type the edges of the bones are beveled and overlap.

e.g.,

the joint between the squamous part of temporal bone and the parietal bone.

(c) Sutura

plana:- In this case the edges of the bones

are plane or slightly roughened.

e.g.,

the internasal suture, or between the horizontal parts of the palatine bones.

(2)

Syndesmosis- In

these type the uniting medium is white fibrous or elastic tissue or a mixture.

e.g., the union of the shafts of the

metacarpal bones and the attachments to each other of costal cartilages.

In a

syndesmosis, when the apposed bones are united by fibrous tissue, such as the fusion of the bodies of

the radius-ulna and tibia-fibula, the original material undergoes ossification

with advancing age, and the process is then

known as synostosis.

(3)

Gomphosis- This

term is sometimes applied to the implantation of the teeth in the alveoli.The

gomphosis is not, properly considered a joint at all, since the teeth are not

parts of the skeleton.

B. CARTILAGINOUS JOINTS

The bones of cartilaginous

joints are united by fibrous cartilage or hyaline cartilage, or a combination of

the two. The amount and kind of movement are determined by the shape of the

joint surface and the amount and pliability of the uniting medium. They are

chiefly classified as:

- Synchondrosis (Hyaline Cartilage Joints)

- Symphysis (Fibrocartilaginous joints)

1. Synchondrosis (Hyaline Cartilage Joints):

This

type of joint (sometimes called a primary cartilaginous joint) is a temporary

one, for the cartilage is converted into bone before adult life. The hyaline

cartilage that joins the bones is a persistent part of the embryonic

cartilaginous skeleton.

The epiphysis and diaphysis of long bone are united by

a cartilaginous epiphyseal plate in the young. Osseous fusion occurs in

adulthood, and a joint no longer exists. Most hyaline cartilage joints are obliterated

by bone when growth ceases.

Examples of hyaline cartilage joints include

epiphyseal plates, the basilar part of the occipital bone with the body of the

basisphenoid bone, the joint between the petrous part of the temporal bone and

stylohyoid bone via the tempanicohyoid cartilage, the costochondral junction

and the inter-mandibular synchondrosis.

2. Symphysis (Fibrocartilaginous joints):

This

joint (sometimes called a secondary cartilaginous joint and referred to

sometimes as amphiarthrosis) represents an articulation in which the contiguous

bones are united by fibrocartilage during some phase of their existence.

Fibrocartilaginous joints include the pelvic symphysis, sternebrae, and joints

between the bodies of the vertebrae. A limited and variable amount of movement

may exist.

C. SYNOVIAL

JOINTS

This group of

joints, also known as diarthrodial joints, are characterized by the presence of

a joint cavity with a synovial membrane in the joint capsule and by their

mobility.

They are often called movable or true joints. A simple joint is one

formed by two articular surfaces; a composite joint, one formed by several

articular surfaces. The following structures enter into their formation of synovial joint:

Articular surface:

The

articular surfaces (facies articulares) are in most cases smooth, and vary much

in form. They are formed of specially dense bone, which differs histologically

from ordinary compact substance. In certain cases the surface is interrupted by

non-articular cavities known as synovial fossae.

Articular Cartilage:

The

articular cartilages, usually hyaline in type, form a covering over the

articular surfaces of the bones. They vary in thickness in different joints;

they are thickest on those which are subject to the most pressure and friction.

They usually tend to accentuated the curvature of the bone, i.e., on a concave

surface the peripheral part is the thickest, while on a convex surface the

central part is the thickest. The articular cartilages are non-vascular, very

smooth and have a bluish tinge in the fresh state. They diminish the effects of

concussion and greatly reduce friction.

Fig:- A Typical True joint (Longitudinal section)

Articular Capsule:

The

articular or joint capsule is, in its simplest form, a tube the ends of which

are attached around the articulating surfaces. It consists of two layers- an

external one, composed of fibrous tissue, and an internal one, the synovial

layer or membrane.

The fibrous layer (membrane fibrosa), sometimes termed the capsular ligament, is attached either close to the margins of the articular surfaces or at a variable distance from them.

Its thickness varies greatly in different situations: in certain places it is extremely thick, and sometimes cartilage or bone develops in it; in other places it is practically absent, the capsule then consisting only of the synovial membrane.

Tendons which pass over a joint may partially take the place of the fibrous layer; in these cases the deep face of the tendon is covered by the synovial layer. Parts of the capsule may undergo thickening and so form ligaments which are not separable, except artificially, from the rest of the capsule.

The synovial layer (membrane synovialis) lines the joint cavity except where this is bounded by the articular cartilages; it stops normally at the margin of the latter.

It is a thin membrane and is richly supplied by close networks of vessels and nerves. It frequently forms folds (plicae synoviales) and villi (villi synoviales), which project into the cavity of the joint.

The folds commonly contain pads of fat, and there are in many places masses of fat outside the capsule which fill interstices and vary in form and position in various phases of movement.

The synovial membrane secretes a fluid, the synovia, which lubricates the joint; it resembles white of egg, but has a yellowish tinge.

It also serves to transport nutrient material to the hyaline articular cartilage. The chemical composition of synovia is similar to tissue fluid. In addition, it contains albumin, mucin and salts and is alkaline.

In many places the membrane forms extra-articular pouches, which facilitate the play of muscles and tendons. The joint cavity is enclosed by the synovial membrane and the articular cartilages. Normally it contains only a sufficient amount of synovia to lubricate the joint.

The fibrous layer (membrane fibrosa), sometimes termed the capsular ligament, is attached either close to the margins of the articular surfaces or at a variable distance from them.

Its thickness varies greatly in different situations: in certain places it is extremely thick, and sometimes cartilage or bone develops in it; in other places it is practically absent, the capsule then consisting only of the synovial membrane.

Tendons which pass over a joint may partially take the place of the fibrous layer; in these cases the deep face of the tendon is covered by the synovial layer. Parts of the capsule may undergo thickening and so form ligaments which are not separable, except artificially, from the rest of the capsule.

The synovial layer (membrane synovialis) lines the joint cavity except where this is bounded by the articular cartilages; it stops normally at the margin of the latter.

It is a thin membrane and is richly supplied by close networks of vessels and nerves. It frequently forms folds (plicae synoviales) and villi (villi synoviales), which project into the cavity of the joint.

The folds commonly contain pads of fat, and there are in many places masses of fat outside the capsule which fill interstices and vary in form and position in various phases of movement.

The synovial membrane secretes a fluid, the synovia, which lubricates the joint; it resembles white of egg, but has a yellowish tinge.

It also serves to transport nutrient material to the hyaline articular cartilage. The chemical composition of synovia is similar to tissue fluid. In addition, it contains albumin, mucin and salts and is alkaline.

In many places the membrane forms extra-articular pouches, which facilitate the play of muscles and tendons. The joint cavity is enclosed by the synovial membrane and the articular cartilages. Normally it contains only a sufficient amount of synovia to lubricate the joint.

The

foregoing are constant and necessary features in all synovial joints. Other

structures which enter into the formation of these joints are ligaments,

articular discs or menisci, and marginal cartilages.

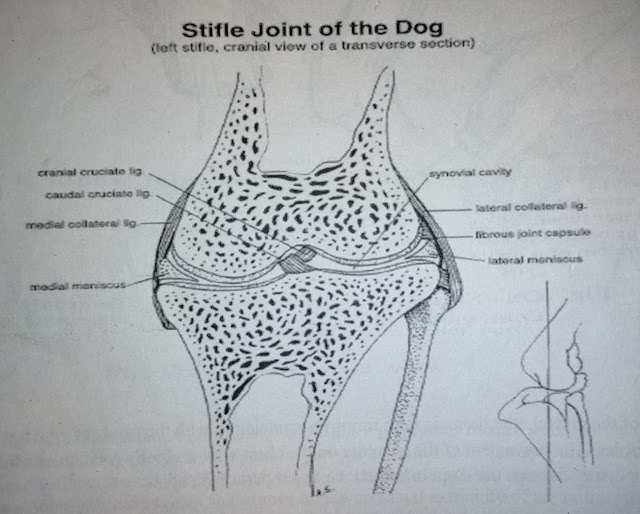

Ligaments:

Ligaments

are strong bands or membranes, usually composed of white fibrous tissue, which

bine the bones together. They are pliable but practically inelastic.

In a few cases, however, e.g., the nuchal ligament, they are composed of elastic tissue. They may be subdivided, according to position, into extra-(periarticular) and intra-(intra-articular) capsular ligaments.

Extra-capsular ligaments are frequently blended with or form part of the fibrous capsule; in other cases they are quite distinct. Those which are situated on the sides of a joint are termed collateral ligaments.

Intra-capsular ligament, although within the fibrous capsule, are not in the joint cavity; the synovial membrane is reflected over them. Those which connect directly opposed surfaces of bones are termed interosseous ligaments.

In many places muscles, tendons and thickenings of the fasciae function as ligaments and increase the security of the joint. Atmospheric pressure and cohesion paly a considerable part in keeping the joint surfaces in apposition.

In a few cases, however, e.g., the nuchal ligament, they are composed of elastic tissue. They may be subdivided, according to position, into extra-(periarticular) and intra-(intra-articular) capsular ligaments.

Extra-capsular ligaments are frequently blended with or form part of the fibrous capsule; in other cases they are quite distinct. Those which are situated on the sides of a joint are termed collateral ligaments.

Intra-capsular ligament, although within the fibrous capsule, are not in the joint cavity; the synovial membrane is reflected over them. Those which connect directly opposed surfaces of bones are termed interosseous ligaments.

In many places muscles, tendons and thickenings of the fasciae function as ligaments and increase the security of the joint. Atmospheric pressure and cohesion paly a considerable part in keeping the joint surfaces in apposition.

Articular Discs and Menisci:

These

are plates of fibrocartilage or dense fibrous tissue placed between the

articular cartilages; they divide the joint cavity partially or completely into

two compartments.

They render certain surfaces congruent, allow greater range

or variety of movement and diminish concussion.

Marginal Cartilage:

A

marginal cartilage (labrum glenoidale, acetabulare) is a ring of fibrocartilage

which encircles the rim of an articular cavity. It enlarges the cavity and

tends to prevent fracture of the margin.

If you have any questions you can ask me on :

mishravetanatomy@gmail.com Facebook Veterinary group link - https://www.facebook.com/groups/1287264324797711/

Twitter - @MishraVet

Facebook - Anjani Mishra

Website: mishravetanatomy.blogspot.com

Post a Comment